Y-a-t-il un pilote dans l'oiseau ?

Lorsque les goélands volent vers l'avant, la mer balaie leur champ visuel d'avant en arrière. Ce "flux optique" leur fournit des informations cruciales sur la vitesse et la hauteur. La perception de ce flux optique serait-elle impliquée dans une sorte de «pilote automatique» ? C'est ce que vient de démontrer une équipe européenne qui a développé un modèle mathématique de contrôle d’altitude appelé «régulateur de flux optique». En effet, ce modèle prédit l’altitude de vol des goélands. Leurs travaux sont publiés dans la revue Royal Society Interface.

Is there a pilot in the bird?

As the gulls fly forwards, the sea below sweeps backward across their field of view. This “optic flow” provides them with crucial information on speed and height. Are the perception of this optic flow involved in some kind of "autopilot"? This has just been demonstrated by a European team that has developed a mathematical altitude control model called "optic flow regulator". Indeed, this model predicts the flight altitude of gulls. Their work will be published online on October 9th, 2019 in the journal Royal Society Interface.

Au milieu des années 2000, le « régulateur de flux optique » avait été mis en évidence chez les insectes ailés. Cette fois, c’est chez l’oiseau que ce même mécanisme de pilotage vient d’être démontré. Pour cela, les chercheurs ont développé un modèle mathématique particulier guidant le vol pour les goélands, puis ont comparé ce modèle aux données de suivi télémétrique (positions GPS en 3D) de plusieurs goélands volant au-dessus de la mer Baltique.

On sait aujourd’hui que les prouesses en vol des oiseaux reposent en partie sur leur capacité à percevoir le flux optique provenant du sol ou de la mer : chez l’oiseau, il existe des neurones spécialisés dans la vision du mouvement. Ainsi, lorsqu'un oiseau vole au-dessus de la mer, l'image de la mer défile d'avant en arrière dans la partie ventrale de son champ visuel, créant ainsi un « flux optique ». Ce défilement optique est égal au quotient de la vitesse horizontale et de l'altitude. Ce que les auteurs appellent un « régulateur de flux optique » est un contrôleur d’altitude qui va maintenir à une valeur constante ce flux optique, donc le quotient vitesse/altitude. Si l’oiseau vient à changer de vitesse, le contrôleur de vol en question agira automatiquement sur sa force de sustentation, ici les battements d’ailes, pour changer d'altitude de manière à maintenir constant le quotient entre ces deux grandeurs. Un animal ajustant son altitude sur la base de ce quotient vitesse/altitude n'a besoin de mesurer ni sa vitesse ni son altitude.

A la base de ces comportements étonnants se trouvent, cachés dans la tête de l’oiseau, des neurones sensibles à des mouvements spécifiques qui sont de véritables capteurs de flux optique. L'équipe européenne (Suède, Pays-bas, Royaume-Uni, France) suggère que les neurones LM (pretectal nucleus lentiformis mesencephali) présents chez les oiseaux, ceux même dédiés à la détection du mouvement, sont sans doute les neurones impliqués.

Lorsqu’un goéland décolle en mer pour revenir à son nid, le goéland bat des ailes : ceci augmente sa vitesse d’avance. Son régulateur de flux optique le mènera à une augmentation de sa force de portance (sustentation), pour maintenir son flux optique à la valeur de référence jusqu’à ce que l’oiseau atteigne sa vitesse de croisière, valeur lui permettant de maximiser l’efficacité énergétique de son vol.

Les auteurs ont également observé statistiquement que plus le vent était favorable (venant de l’arrière), plus les oiseaux augmentaient leur altitude, et réciproquement, ce qui s’explique également par un pilote automatique basé sur un « régulateur de flux optique ». Le contrôleur de vol proposé, pourtant fort simple, permet de rendre compte de 50 ans d'observations en ornithologie, souvent surprenantes et conduites (par exemple au radar) dans les années 60. Il permet d'expliquer le fait que les oiseaux effectuant un vol directionnel (une migration, ou un retour au nid) volent à basse altitude par vent de face et s'élèvent par vent arrière.

In the mid-2000s, the "optic flow regulator" was demonstrated in winged insects. This time, it is with birds that this same control system has just been demonstrated. Indeed, the researchers developed a particular mathematical model guiding the flight for gulls, then compared this model to telemetry tracking data (3D GPS positions) from several gulls flying over the Baltic Sea.

We now know that birds' prowess in flight depends in part on their ability to perceive the optic flow from the ground or the sea: in birds, there are neurons specialized in the visual processing of movement. Indeed, when a bird flies over the sea, the image of the sea scrolls from front to back in the ventral part of its visual field, creating an "optic flow". This optic flow is equal to the quotient of forward velocity and altitude. What the authors call an "optic flow regulator" is an altitude controller that will maintain this optic flow at a constant value, thus the forward velocity/altitude quotient. If the bird is changing speed, the flight controller in question will automatically act on its lifting force, in this case the wing flaps, to change altitude in order to maintain constant the quotient between these two values. An animal adjusting its altitude on the basis of this forward speed/altitude quotient means that the animal does not need to measure its own speed or altitude.

If gulls would have maintained a constant altitude, then their altitude would not increase in proportion to their ground speed. However, it is precisely this proportionality that is statistically significant and that the authors have observed and demonstrated in gulls: an "automatic pilot" therefore adjusts their altitude in proportion to their speed.

At the root of these amazing behaviours are neurons hidden in the bird's head that are sensitive to specific visual motion and are true optic flow sensors. The European team (Sweden, Netherlands, United Kingdom, France) suggests that LM neurons (pretectal nucleus lentiformis mesencephali) present in birds, these dedicated to motion detection, may be the responsible neurons.

When a gull takes off at sea to return to its nest, the gull flaps its wings: this increases its forward speed. Its optic flow regulator will lead it to an increase its lifting force, to maintain its optic flow at the reference value until the bird reaches its cruising speed, a value that will allow it to maximize the energy efficiency of its flight.

The authors also observed statistically that the more favourable the wind (from behind), the more the birds increased their altitude, and vice versa, which is also explained by an autopilot based on an "optic flow regulator". The proposed flight controller, although very simple, makes it possible to report on 50 years of ornithological observations, often surprising and conducted by radar in the 1960s, for example. It explains the fact that birds flying in a directional flight (a migration, or a return to the nest), fly at low altitude in headwinds and rise in tailwinds.*

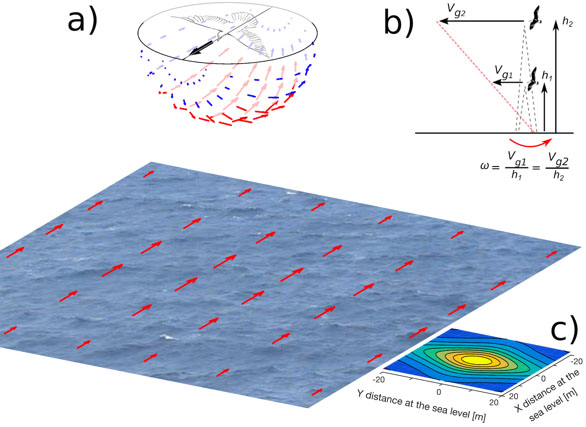

Figure : a) Un goéland volant au-dessus de la mer génère un champ vectoriel de flux optique. Un tel champ vectoriel est perçu par un goéland en fonction des contrastes créés notamment par les crêtes des vagues.b) L'amplitude du vecteur de flux optique est déterminée par la vitesse d’avance du goéland et son altitude. Si le flux optique est maintenu constant en ajustant l'altitude, l’altitude aura toujours tendance (à travers la dynamique de l'oiseau) à être proportionnel à la vitesse d’avance (seule une combinaison linéaire - ligne pointillée rouge - entre l’altitude et la vitesse d’avance est asymptotiquement possible). c) Amplitude du flux optique dans le champ de vision ventral de l’oiseau à une hauteur de 10m : l'amplitude du flux optique ventral est maximale à l’aplomb.

a) A gull flying over the sea generates a vector field of optic flow. Such a vector field is perceived by a gull according to the contrasts created by the wave crests.(b) The amplitude of the optic flow vector is determined by the gull's forward speed and altitude. If the optic flow is kept constant by adjusting the altitude, the altitude will always tend (through the dynamics of the bird) to be proportional to the forward speed (only a linear combination - red dotted line - between the altitude and the forward speed is asymptotically possible).(c) Amplitude of optic flow in the bird's ventral field of view at a height of 10m: the amplitude of the ventral optic flow is maximum downwards.

Pour en savoir plus :

Optic flow cues help explain altitude control over sea in freely flying gulls

Serres JR, Evans TJ, Åkesson S, Duriez O, Shamoun-Baranes J, Ruffier F, Hedenström A.

J. R. Soc. Interface 09 October 2019 . doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2019.0486